How Change is Made: Four Levels of Education Advocacy

April 25, 2023

A Guide to Curriculum Changes with Associate Superintendent Amy LaDue

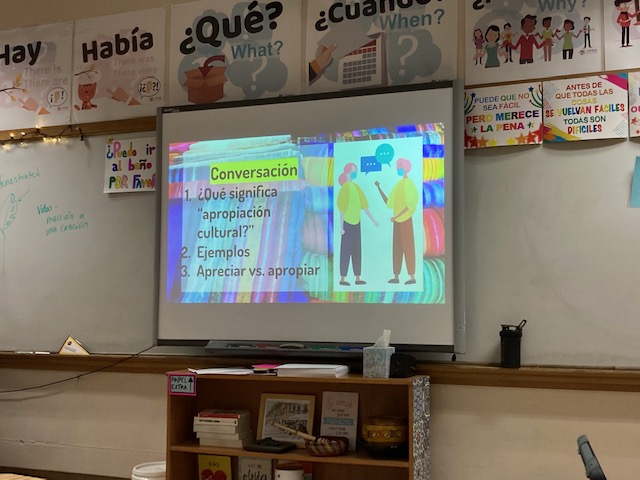

As the push for greater equity in education continues, many look to curriculum as a source of well-needed change. Curriculum changes, however, are more complex than one might think, Associate Superintendent Amy LaDue explained.

While Minnesota has adapted some of the common core standards that have been established on the national level, the state standards are relatively flexible, largely focused on reading, language arts, math, and science.

“The state of Minnesota really leaves districts to create local standards,” said LaDue, “ and they encourage [districts] to align with the national standards, which is what we’ve done as a district.”

Minnetonka’s Policy #603 outlines the standards for curriculum review and improvement, implemented at the district level. The cycle of curriculum review occurs every 10 years at the state level, but yearly at the district level.

“When we talk about how to develop our curriculum,” LaDue said, “we think about, you know, what do we want kids to learn? What does that learning look like? And then how will they know if they learned it?”

Who is it that asks and answers these questions? The answer is a lot of people. “More goes into curriculum than I think is really seen at the surface, and it’s really complex — it’s not straightforward,” LaDue said. “There’s a lot of inputs and a lot of outputs.”

One input is feedback from teachers and educators. “[We have] a district Teaching and Learning advisory [with] several teachers that represent different programs,” LaDue said. “They [serve as] a broad voice, and the department chairs represent their specific department, and are responsible for [meeting] with their department to gather feedback.”

Teachers are given some wiggle room to test out new texts or sources, based on their assessment of student needs. According to LaDue, teachers can pilot a new text in any given year, so long as it teaches students the required skills for their grade level. If they wish to continue teaching that new text, it has to be approved through the curriculum development process, to be adopted by August of the following year.

Teachers are not the only input source; students are encouraged to share their thoughts as well. “One of the things that’s really been elevated in the new language arts standards is more student choice,” she said. LaDue said she thinks an important aspect of curriculum development is providing students with the opportunity to see themselves and their peers in the content they are learning. As curriculum is routinely rethought, the district continues to think about whether “every student [sees] themselves positively reflected in novels,” and “maybe sometimes negatively reflected – proportionately.”

If students find this to be untrue, a good way to raise the issue is by discussing it with a teacher or department chair, who can then relay it to the Director of Curriculum in the form of feedback, which they will certainly take into consideration.

“It’s exciting when we can be responsive,” said LaDue, “when we know a need exists and we can, with confidence, put in place a stronger curriculum and provide teachers with the professional learning time so that they’re equipped to deliver.”

An Interview with Deepti Pillai, MCEE Co-founder

What is your role in the MCEE?

In 2020, I helped co-found it, and since then the way that it’s structured is that we just have our core leaders, so I’m just one of the leaders in the group.

Could you summarize some of the MCEE’s initial goals?

We have a list of imperatives, and there were eleven or twelve to begin with in 2020. Some of them were achieved — some of the ones we had actually gotten established by the school board were ‘equity training for teachers’, and ‘recruiting more BIPOC teachers’.

What was the process of getting the school board to implement them?

We went to several school board meetings, and at school board meetings — anyone can speak at them — if there was an agenda item that was regarding something that was similar to some of our imperatives, that’s when we would jump in. We would go to consistent meetings, and by doing so, we were able to propose our imperatives. The school board also has speaking sessions — it’s a round table discussion where you can speak directly with the board, and so we went to some of those as well, where we were able to discuss and pitch our imperatives.

How did it feel to get those things accomplished?

I feel like with an organization like the MCEE it’s really easy to say, like, ‘oh, community outreach is working well, lots of people came to our protests and rallies,’ but it’s so nice to get recognized by the administration that we’re directly trying to contact. It’s such a tangible sign of success.

Assistant Principal Smasal Wants Student Voices Heard

The process of equitable education advocacy, at least in the Minnetonka school district, is often student-led. This does not mean that staff and administration play no role in it: Assistant Principal Smasal, coordinator of the Student Belonging Committee, said she views herself as a facilitator for student expression. “My job is really to gather student voices so that we can create a healthy, inclusive culture and climate at the school,” she said.

Smasal joined the district two years ago, in 2020, a remarkably tumultuous time for both education and equity movements. The recent murder of George Floyd and the onset of COVID-19 weighed heavily on student minds. “It rocked the world, it really did,” said Smasal, “I think we as a system learned that students need voice, they need an outlet, a space to just be with one another in times of need.”

From that struggle, Smasal said she believes the relationship between students and administration grew stronger. “We all deal with [heavy emotions] differently, including staff, but in my perspective it really opened the door to communication.”

Looking forward to the future of advocacy work in Minnetonka, Smasal said she’s “excited about the cultural fair, and honing in on Educate and Celebrate,” a project she is facilitating that utilizes Schoology communications to teach the community about important cultural events and minority groups.

“[Advocacy] is all about relationships,” Smasal said, “not only between us and students, but I can speak on behalf of administration when I say it’s amongst students as well.” Student-led projects like the cultural fair are the future, and Smasal aims to support them along the way.